Blog Archives

Have You Ever Fallen Victim of Distorted Perception?

It’s all about perception. Our brain understands any situation based on what it’s been trained to see and what it thinks is out there [1]. Two chess players can see the same position and come away with vastly different perceptions.

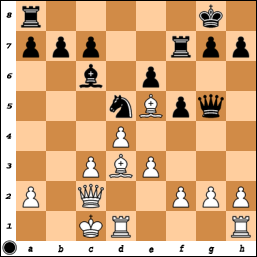

I have posted the below position from Teichmann – Chigorin, Cambridge Springs 1904, in a few Facebook groups inviting comments about how valuable the e5-bishop really is – is it “good”, or “bad”?

Well, most chess books tell us about the center very much the same (for example, see [2]), and based on that amputated view of reality, the e5-bishop in the diagram below should be perceived as dominant and strong.

Actually, this bishop is miserable!? – Really, you gotta be kidding me!

A powerful bishop freezing the blood of the enemy, or just a fake? (Thanks to Samuel Bak for another great piece of chess art, "Bishop, Knight, Rook")

What’s wrong with the bishop “strong”? What is missing from the picture if we can’t seem to see things clearly here? Could it be that our brain doesn’t perceive something very important, perhaps something we haven’t been given due attention during our primary chess education? Maybe something we don’t take into picture consistently every time we think the next move, and we should?

To find out, let’s take a look at the game (with the game commentary from Vladimir Alatortsev, [3])

Richard Teichmann – Mikhail Chigorin

Cambridge Springs 1904

1. d4 d5 2. c4 Nc6 3. Nf3 Bg4 4. cxd5 Bxf3 5. dxc6 Bxc6 6. Nc3 e6 7. Bf4 Nf6 8. e3 Bb4 9. Qb3 Nd5 10. Bg3 O-O 11. Bd3 Qg5 12. Qc2 f5 13. Be5 Rf7 14. O-O-O Bxc3 15. bxc3

A very instructive position. White has a centralized bishop occupying a classic outpost. Moreover, it’s eyeing at the black king’s position. Yet, the bishop can’t be considered as an attacking piece. Why? Because it’s detached from the rest of the army. Even its pressure at g7 is fictitious as the bishop isn’t coordinated with other team members. For that purpose, White needs to have other pieces taken part in the attack, by playing Rg1 and g2-g4 to open the g-file, for instance. The pressure on g7 will mean something only after the rook joins the attack. But White simply has no time for it as his king needs defense. And for that the bishop is better placed at b2.

Here’s Botvinnik’s comment: “The basic weakness of White’s position is the “strong” position of his bishop at e5, even though it is evident that White pinned all his hopes to it! For the bishop is badly placed at e5, as it can’t share in the defense of its king when Black begins an energetic counter-attack… only four moves were necessary and Black’s attack was irresistible,” [4]

It’s a completely different story with the black knight which too is occupying a central position. The knight soon becomes one of principal attackers, together with the black queen, bishop and b-pawn. The knight hasn’t established an effective coordination with friendly troops yet, however, Black can ensure it much faster than White on the K-side (Rg1, g2-g4). The coordination of pieces is dynamic in nature.

15. …b5! 16. Rhg1 Qe7 17. Rdf1 Qa3+ 18. Kd2 b4! 19. c4 Ba4 20. Qb1 Nc3 21. Qa1 Rd8!

Almost all black pieces including b-pawn have achieved a harmonious cooperation. They are all after the white king. Coordination between white pieces is deteriorating with each move.

22. g3 Ne4+ 23. Ke2 Nc5 24. Qb1 Nxd3 25. Qxd3 Qxa2+ 26. Kf3 Bc2 0-1

Black pieces have completed a successful attack on the white king. On the other hand, the “strong” e5-bishop has never taken part in the battle. We’ve seen an exemplary coordination of black troops, and a lack of coordination on the other side. Formally speaking, the position of the e5-bishop was ideal, but the form was at odds with inner meaning of the situation – the bishop has not played part in defending the Q-side at all.

In a game of chess, there should not be spectators. If chessmen of one side are not participating in offensive operations (piece cooperation in attack), they should be standing on defensive positions (piece cooperation in defense).

* * *

Let’s remind ourselves once again of what the great Capablanca told us:

“The main thing is the coordination of pieces, and this is where most players are weak. Many try to attack with one piece here and another piece there without any concerted action, and later they wonder what is wrong with their game. You must coordinate the action of your pieces, and this is a main principle that runs throughout“, Capablanca, My Chess Career.

On the scale of the value of pieces (see section E-2-v), perhaps the coordination should move up to the top of the list… After all, it all may be about the coordination of troops, piece harmony, team play, working together. Chess is a team sport…

* * *

Sources and references:

[1] How your chess vision works, “What actually happens under your skull when you read a chess position?”

[2] “Any piece placed in the center is controlling more squares than it would elsewhere, which means that this is where it possesses its greatest fighting value. Furthermore it is from the center that pieces can be transferred to either of the flanks in the smallest number of moves,” Isaac Lipnitsky, Questions of modern chess theory, Quality chess, 2008, p.14 (this widely accepted view on the value of a centralized piece doesn’t take into account that piece value and dynamic position evaluation are dependent on chess contacts, that is, how pieces interact during the game and what kind of relationships they establish at any time)

[3] V. A. Alatortsev, Coordination of pieces and pawns in the game of chess, Moscow, Fizkultura and sport, 1956, p.41

[4] M. Botvinnik, One hundred selected games, Dover publications, p.17

___________________________________________________________________________________

Follow @chessContactI give a 30-minute free consultation on how to get started in chess most effectively to get your game on the fast track. Forget about a boring and confusing 30-page introduction with all those rules on how pieces move, en-passant, 50-move draw, threefold repetition rule etc., most chess books start with.

Let’s go right away to the heart and core of the whole chess thing…

You may contact me at iPlayooChess(at)gmail(dot)com

What Actually Happens Under Your Skull When You Read (a Chess Position)? How Your (Chess) Vision Works?

What chess experts see/recognize/understand effortlessly on the board and chess novices don’t?

What makes the difference?

How can you get a novice on the fast road to developing a good chess vision?

Persian bronze gaming pieces (6th-7th c. AD)

Persian bronze gaming pieces (6th-7th c. AD)

It is all about perception. We discussed last time that perceiving spatial and especially functional relationships between objects in a visual environment is the key to understanding the meaning of a situation and how to react to it.

To better understand where the problem lies let’s take a look at how perception occurs. There are three steps involved in visual processing:

Sensation: we capture external visual information and convert it into head-speak, that is brain-friendly electrical language.

Routing: once translated, the information goes to the supervisor center (thalamus) which in turn sends it off to the brain’s increasingly complex higher regions for further processing.

Perception: at this final step of sophisticated processing in association cortices we begin to perceive what our senses have given us. These regions use both bottom-up and top-down processing. The two work together to help us recognize the world.

Reading a sentence

Here’s an example which beautifully illustrates bottom-up and top-down interaction.

After your eyes read the sentence and the thalamus has spattered various aspects of the sentence all over your skull, bottom-up processors go to work by greeting the sentence’s visual stimuli, its letters and words. An upside down arch becomes the letter “U”, combinations of straight lines and curves become, say, word “Uagadugu” (by the way, this is my favorite vacation spot – just kidding).

Now comes top-down processing where the previous detailed “report” is interpreted and analyzed to get the meaning out of it in order to respond to the original stimulus, or a change in the environment (remember S->R, stimulus->response mechanism?). This is done in light of pre-existing knowledge, or stored patterns (schemas), mental representations of what we know and expect about the world. Schemas can bias our perception toward one recognition or another by creating a perceptual set, that is a readiness to perceive stimuli in a certain way. These expectations operate automatically, whether we are aware of them or not.

Given that people have unique experiences, they bring different interpretations to their top-down analysis, so two people can see the same input and come away with vastly different perceptions. Think a chess expert and a novice.

Pieces are just placeholders for certain functions. Playing Chess, by Brett Dugan

Pieces are just placeholders for certain functions. Playing Chess, by Brett Dugan

Chess analogy

In chess, what is analogous to words? Chess pieces.

During the bottom-up stage we scan the board to see how all pieces are positioned in their battling space. In our mind’s eye we need to see each piece together with its aura, or lines of power emanating from it, as one inseparable entity. Thus we are becoming aware of how pieces are interacting, with both friendly and enemy ones, and of spatial relationships and connections between them.

But what gives words and pieces their meaning? Where does this meaning come from?

What is the difference between playing well and aimlessly moving the pieces (pushing wood)?

The top-down process kicks in by recognizing functional relationships, or roles pieces have in the current context. Some pieces are attacking enemy pieces and/or important squares on the board restricting them, others are supporting friendly pieces, or blocking attack on them coming from opposing troops. This brings the meaning into the picture. Previous experience helps evaluate the situation adding up new layers of meaning.

Our motivation and expectations also get in affecting the perception. For example, if this is the last round and you need to win, you are likely to be in aggressive mode where you tend to perceive more of attacking aspects of the position, neglecting potential dangers.

With a growing perception your understanding deepens too. However, understanding a word is not a mental state, event or process, but an ability to use it in certain ways for certain purposes, just as knowing how to play chess is knowing how to move the pieces in conformity with the rules of chess in pursuit of the goal of winning. In both cases mastering technique is necessary (and this is where mastering strategy and tactics, as its building blocks, get in).

Log Chess Set, by Peter Marigold

Log Chess Set, by Peter Marigold

Good 20/20 or protracted and poor chess vision? Which one?

We see now how chess experts and novices have different interpretations of what they see on the board. Ability to recognize visual patterns and unconsciously follow (previously learned and stored) action patterns associated with them makes the difference.

Now is crystal clear why we need to start teaching with contacts and not with chess moves as the traditional teaching does. We need to develop good spatial and functional recognition skills if we want to strengthen bottom-up visual processing and create a good chess eye and strong board vision real quick, early in the learning process. As vision is the key to understanding and acting in the world, everything else follows on from it.

Teaching how to move pieces does very little to develop a good chess eye. It actually sends wrong messages to the brain what really important is in the game. As the brain willy-nilly starts creating habits (bad ones, of course) in order to be able to respond with automaticity later on (economy of time and energy!), an ineffective, and sometimes even dead-wrong perceptual set develops.

We are all going through the first period of our chess education mostly unaware of what’s going on on the board, not seeing attacks raging all around the place with our Queen maybe lost at move three (remember the game we saw before: 1.e4 d5 2.Bd3 Bg4 3.exd5 Bxd1).

But this period should be fairly short and end within roughly two months of the start of learning. Sadly, the players from the above game had been in chess for more than a year when they played it back then.

Definitely, they had been infected with that widespread chronic disease: poor chess vision, which sometimes turns to chess blindness.

Looking at that game again, something’s really rotten in our chess kingdom… the early teaching in fact.

Good news is that there is an effective cure available: contacts treatment!

* * *

SOURCES:

1) John Medina, “Brain Rules: 12 Principles for Surviving and Thriving at Work, Home, and School”

2) Ludwig Wittgenstein, “Understanding and Meaning”

3) Douglas Bernstein, “Essentials of Psychology ”

___________________________________________________________________________________

Follow @chessContactI give a 30-minute free consultation on how to get started in chess most effectively to get your game on the fast track. Forget about a boring and confusing 30-page introduction with all those rules on how pieces move, en-passant, 50-move draw, threefold repetition rule etc. most chess book starts with.

Let’s go right away to the heart and core of the whole chess thing…

You may contact me at iPlayooChess(at)gmail(dot)com

Why is the Traditional Way of Teaching Chess Fundamentally False?

How did we all get started in chess? Traditionally, we were shown “the moves first”.

Yet, by a curious paradox, it appears to be fundamentally false (Nimzovich, Shakhmatny Listok, 1929). We call it a paradox, but it may just be that there is something we really don’t understand about it – once uncovered, it’s no more a paradox.

Actually, the way how we teach chess (and not only chess!) doesn’t align with how learning occurs and how neuropsychology, educational psychology, and learning theory explain it. We simply ignore how human brain works and how it acquires new knowledge efficiently.

The traditional way of teaching is rotten. The first, or primitive brain that is mostly responsible for learning is typically excluded from the process. Next, initial activities (in chess it is “showing the moves”) are not meaningful and the learner understands neither why they are doing them, nor what their purpose and usefulness is. The latest scientific research shows that meaning-based instruction is critical to development of any skill. As a result, what we teach doesn’t get the learner on the fast track. They don’t see any progress. They lose confidence. Ultimately, too often they give up chess altogether.

If we really want to speed up learning curve in chess we definitely need to change something. We need to replace “showing the moves first” as it is apparently ineffective and inefficient.

This post and two upcoming ones are intended to demonstrate why the traditional method of teaching chess seems to be entirely flawed. First, here we will take a short look at what neuroscience tells us about the basics of learning. Then, later on, we are going to: a) apply what we say today to chess learning, b) present an article by GM Aaron Nimzovich, written 82 years ago in the Russian “Little Chess Paper” that shows an entirely different approach to chess teaching and learning.

How humans behave. Stimulus-Response mechanism

First we need to know how humans (and other species) act and behave. Behavior is an organism’s activity in response to external or internal stimuli. For example, plants turn toward the Sun. The purpose – to survive by making their food using sunlight (photosynthesis). The mechanism is basically this: stimulus -> some nervous system activity -> response.

In chess, the stimulus, or change, is the move your opponent just made. Follows a mental thought process which produces your next move, or response.

With a repeated exposure to a stimulus, we create a habit, or routine behavior that we replay regularly and which tends to occur subconsciously. There must be some evolutionary advantage here. By having habits:

a) we don’t have to engage the brain all the time (which takes time and energy),

b) we can avoid risks and dangers by sticking to the safe, proven path.

It is very important to stress that there is a strong link between the habit formed and the survival. All our behavior is goal-directed and purpose-driven. This is hard wired in all species.

Importance of vision

The main role of our senses is to allow us to monitor the environment and to react to it in ways conducive to survival. Our brain activity is largely influenced by vision. Through the process of perception we become aware of objects, relationships and events which enables us to organize and interpret the stimuli received into meaningful knowledge.

Exposed to a stimulus via visual faculty, the brain, which works by analogy and metaphor, begins to look for similarities, differences, or relationships between new information and stored patterns. When it matches the same or similar pattern, a response is executed based on the previously learned, expected behavior.

Why and how learning happens

But what happens when the brain is not familiar with a new stimulus? The process of learning initiates. We use past memories and prior experiences, things we already know (already wired connections between neurons), in order to build or project a new concept. By Law of Association we use what we know to understand what we don’t know. We use existing brain circuits to make new brain circuits.

Now say we want to learn how to play chess. And as we may expect, the first thing they show us is how pieces make movements over the board: Rook goes like this, Bishop goes like that…

Can you connect this to anything you’ve known previously? No way. What is the purpose of making moves? No one understands.

This explains why most of us stay woodpushers, or end our chess careers prematurely by giving up completely as we don’t see the meaning early in the process. Only few get out of the vicious circle and become successful.

Ironically, thinkers from Wittgenstein to Saussure used chess as a key metaphor to illustrate how meaning is produced…

To be continued…

___________________________________________________________________________________

Follow @chessContactI give a 30-minute free consultation on how to get started in chess most effectively to get your game on the fast track. Forget about a boring and confusing 30-page introduction with all those rules on how pieces move, en-passant, 50-move draw, threefold repetition rule etc. every chess book starts with.

Let’s go right away to the heart and core of the whole chess thing…

You may contact me at iPlayooChess(at)gmail(dot)com